By Matt Ford | Published: July 02, 2008 - 12:01PM CT

Launched

on August 20th, 1977, Voyager 2 was sent out to study

the solar system and beyond. Just a hair over 30 years later, it

reached

what is known as the termination shock. The sun is constantly spewing

out particles in all directions; as these particles move through the

solar system, they are known as the solar wind. This wind pushes back

against the interstellar plasma that exists throughout the galaxy.

Launched

on August 20th, 1977, Voyager 2 was sent out to study

the solar system and beyond. Just a hair over 30 years later, it

reached

what is known as the termination shock. The sun is constantly spewing

out particles in all directions; as these particles move through the

solar system, they are known as the solar wind. This wind pushes back

against the interstellar plasma that exists throughout the galaxy.

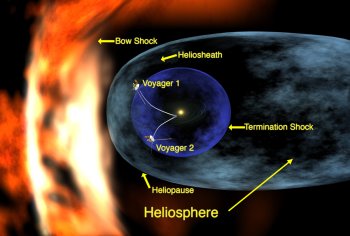

At the end of the solar system, the solar wind finally begins to lose out and its speed drops below the speed of sound (relative to the interstellar medium), resulting in a roughly spherical shell known as the termination shock front. Almost 30 years to the day after it launched, between August 31st and September 1st of last year, Voyager 2 crossed the termination shock, and captured a great deal of information in the process.

This week's edition of Nature contains a series of five papers, plus a News and Views article, on the data sent back by Voyager 2 as it crossed the termination shock. When Voyager 1 crossed this region of space a few years prior, telemetry outages caused it to fail to send data back to Earth, leaving Voyager 2 as the only realistic hope for directly observing the physics that occur in this intermediate region of space (at least for many years to come). Each of the papers examined a slightly different type of measurement; since Voyager 2 had functional plasma sensors, magnetic field detectors, and a host of other equipment, it was able to directly gather a wealth of data to send back to Earth.

Given the difference in times and locations, it was expected that the two probes would encounter the termination shock at different radial locations. Before Voyager 2 crossed the termination shock, scientists observed interstellar hydrogen and helium flow directions; from these it was thought that the interstellar magnetic field is tilted about 60o relative to the flow direction. This should result in the southern portion of the termination shock being closer to the sun when compared to the northern portion of the shock. Voyager 2's crossing at about 45o to the south in heliolongitude terms confirmed this idea. The probe encountered the termination shock 10 AU closer to the sun than Voyager 1 did (one astronomical unit is the average distance between the Earth and the Sun). Voyager 2 crossed at 83.7 AU, while Voyager 1 crossed at 94.1 AU. When correcting for changes in solar wind pressure due to solar cycles, astronomers conclude that the termination shock has a seven to eight AU asymmetry in its shape.

Prior to the actual event, researchers had

expected a fairly simple crossing, with the probe moving from a

region where the solar wind was supersonic to one where it was

subsonic. What they found instead was a "complex, rippled, quasi-perpendicular

supercritical magnetohydrodynamic shock of moderate strength undergoing

reformation on a scale of a few hours." Instead of moving through

the shock front once, Voyager 2 underwent five distinct crossings over a two day period. This was due to the dynamic nature of

termination shock fluctuations; in fact, the time between

crossings is on the order of magnitude expected for ripples propagating through

the shock.

Prior to the actual event, researchers had

expected a fairly simple crossing, with the probe moving from a

region where the solar wind was supersonic to one where it was

subsonic. What they found instead was a "complex, rippled, quasi-perpendicular

supercritical magnetohydrodynamic shock of moderate strength undergoing

reformation on a scale of a few hours." Instead of moving through

the shock front once, Voyager 2 underwent five distinct crossings over a two day period. This was due to the dynamic nature of

termination shock fluctuations; in fact, the time between

crossings is on the order of magnitude expected for ripples propagating through

the shock.

Various instruments searched for the force that is holding the shock front back, and it was found that energized "pickup ions" play a major role in the dynamics of the termination shock. These pickup ions are interstellar neutral atoms that are caught up in the solar wind and have become accelerated and ionized. One paper concluded that these ions account for more of the nonthermal partial pressure holding back the interstellar plasma than either the thermal plasma pressure or the pressure due to the magnetic field.

Other papers asked how similar this shock front is to other shock fronts in the solar system. Voyager 2 generated data that revealed the spectrum produced by the electric field of the plasma in the area near the termination shock. It was found to be qualitatively similar to the observed bow shocks upstream of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

One difference between this set of observations and the data gather by Voyager 1 was that Voyager 1 saw anomalous cosmic rays as it neared the shock, and these did not peak when it crossed the shock. Voyager 2, on the other hand, saw no evidence of these anomalous cosmic rays, so their origin remains a mystery for now. Researchers feel that once both craft are clearly through to the heliosheath—the region beyond the termination shock—during the solar minimum, both can begin to measure the relative intensity gradient between the anomalous cosmic rays and more standard galactic cosmic rays.

Voyager 2's crossing of the termination shock represented a huge advance in our understanding of the geography of the solar system. Since no data was returned from Voyager 1, this represents the only realistic possibility for humanity to gather in situ data from this region of space for many years. While both probes may be beyond the influence of most of the solar wind, their time remaining in the heliopause will give them the chance to send back even more information that we already have.

Nature,

2008. DOI: 10.1038/nature07024

Nature,

2008. DOI: 10.1038/nature07030

Nature,

2008. DOI: 10.1038/nature07022

Nature,

2008. DOI: 10.1038/nature07029

Nature,

2008. DOI: 10.1038/nature07023

(DOI links will not go live until Thursday)

* Click the first image for a full size version

Filed under: Voyager, Astrophysics, Space weather, Science

Apple has given the date and time it that applications submitted by developers that desire to have them included in the launch of the App Store.

Whitepapers from Intel:

Reader comments

jcarroll

July 02, 2008 @ 12:09PM

Yoweigh

July 02, 2008 @ 12:13PM

InThane

July 02, 2008 @ 12:15PM

Tap56

July 02, 2008 @ 12:30PM

mujadaddy

In other words, hold your breath, PLEASE.

Ontopic, that's fkn cooool.

July 02, 2008 @ 12:38PM

Soriak

July 02, 2008 @ 12:45PM

kemche

very cool.

KG

July 02, 2008 @ 12:55PM

bjaffee

July 02, 2008 @ 01:04PM

zeotherm

The way it should be (again, I am not 100% so if there are any space weather experts reading, feel free to correct me) Is that with in the solar system the solar wind pushes out against the intergalactic medium forming a roughly spherical boundary around the entire system. Beyond that is the heliosphere, where intergalactic medium and solar wind particles co-mingle, then it eventually trails off (ending at another roughly spherical boundary called the heliopause) to be just intergalactic medium/plasma/space.

Honestly, I think I have seen that image used before, and it was simply poorly modified for this instance, and I did not give it enough thought

July 02, 2008 @ 01:19PM

nafhan

Obviously, Douglas Adams Hitchikers Guide (Restaurant at the End of the Universe), but also Larry Niven's Protector (there was actually a lab, of sorts, at the end of the solar system). Very different books, but both worth reading. One's comedy scifi and the other is some very interesting hard scifi.

July 02, 2008 @ 01:32PM

l8gravely

It looks to be at Pluto (36AU) at 2015, so it will probably not be out to the 85AU range until 2025 at a guess. The mission guide has a wealth of information, but doesn't mention the Heliosphere that I see in a quick perusal.

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/common.../NH_MissionGuide.pdf

July 02, 2008 @ 01:38PM

jcarroll

Sniff (pass hankies please)

July 02, 2008 @ 02:02PM

Hat Monster

You're assuming the Sun is stationary relative to the interstellar medium. It is not, far from it. I don't have the relative velocities to hand, but they're in the order of kilometers per second.

July 02, 2008 @ 02:03PM

Alarmist

I'd probably still have less than 1 buck.

July 02, 2008 @ 03:02PM

kcisobderf

July 02, 2008 @ 03:26PM

skicow

LOL. Nice.

This is very very cool that Voyager 1&2 are still useful to scientist even today...Voyager was what got me interested in space (I was seven when Voyager 2 launched), then after Sagan's Cosmos TV shows that was all she wrote...only thing that I truly want to do before I die is to be launched into space.

July 02, 2008 @ 03:32PM

jinzou-ningen

Damn Klingons!!!

July 02, 2008 @ 03:39PM

Penforhire

July 02, 2008 @ 04:11PM

Bad Monkey!

Do the Mars Rovers exceeding their planned lifetimes about 10 times over count? Ulysses working for about 18 years, and just now getting shut down due to the age of its RTG? Cassini launched in 97 and still going strong? Mars Phoenix lander executing a tricky powered descent onto the Martian surface, something that hasn't been tried since the Viking landers?

I see comments like your all the time, and I know you're trying to be witty, but really, it just comes off as willfully ignorant.

July 02, 2008 @ 06:02PM

zeotherm

July 02, 2008 @ 07:59PM

Nyx

The Sun orbits the galactic center in around 230 million (Earth) years, making the Sun 20 Gal years old

Cant remember what the rest of the interstellar medium's velocities where but i DO recall that the gas clouds were supposed to be moving slower than the stars.

Oh and there was supposed to be some oscillatory motion of the Sun thru the plane of the galactic disc.

July 02, 2008 @ 10:24PM

Nyx

Indeed, half crippled, 13 billion km from us but still sending us info...

July 02, 2008 @ 10:32PM

phillfri

July 03, 2008 @ 02:37PM

PsionEdge

July 03, 2008 @ 03:08PM

Super Charlie

July 03, 2008 @ 03:52PM

Virogtheconq

http://arstechnica.com/journal...e.admin/m-blog/post/

Maybe the intended target was here?

July 03, 2008 @ 04:00PM

zeotherm

Yeah, I think the second link is the one that was intended to go in there. I'll fix it when I get home tonight

July 03, 2008 @ 04:07PM