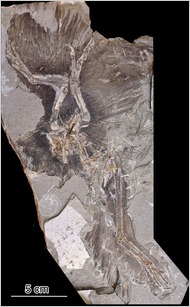

Until last week, paleontologists could offer no clear-cut evidence for the color of dinosaurs. Then researchers provided evidence that a dinosaur called Sinosauropteryx had a white-and-ginger striped tail. And now a team of paleontologists has published a full-body portrait of another dinosaur, in striking plumage that would have delighted that great painter of birds John James Audubon.

RSS Feed

Readers' Comments

Readers shared their thoughts on this article.

“This is actual science, not ‘Avatar,’ ” said Richard O. Prum, an evolutionary biologist at Yale and co-author of the new study, published in Science.

Dr. Prum and his colleagues took advantage of the fact that feathers contain pigment-loaded sacs called melanosomes. In 2009, they demonstrated that melanosomes survived for millions of years in fossil bird feathers. The shape and arrangement of melanosomes help produce the color of feathers, so the scientists were able to get clues about the color of fossil feathers from their melanosomes alone.

That discovery prompted British and Chinese scientists to examine fossils of dinosaurs that are covered with featherlike structures. The 125-million-year-old species Sinosauropteryx, for example, has bristles on its skin, and scientists found melanosomes in the tail bristles. They concluded that the dinosaur had reddish-and-white rings along its tail.

The discovery, which the researchers reported last week in Nature, supports research showing that birds are dinosaurs, having descended from a group of bipedal dinosaurs called theropods.

Dr. Prum and his colleagues, meanwhile, had set out on a similar quest. “We had a dream: to put colors on a dinosaur,” said Jakob Vinther, a graduate student at Yale.

Working with paleontologists at the Beijing Museum of Natural History and Peking University, the researchers began to study a 150-million-year-old species called Anchiornis huxleyi. The chicken-sized theropod was festooned with long feathers on its arms and legs.

The researchers removed 29 chips, each the size of a poppy seed, from across the dinosaur’s body. Mr. Vinther put the chips under a microscope and discovered melanosomes.

To figure out the colors of Anchiornis feathers, Mr. Vinther and his colleagues turned to Matthew Shawkey, a University of Akron biologist who has made detailed studies of melanosome patterns in living birds. Dr. Shawkey can accurately predict the color of feathers from melanosomes alone. The scientists used the same method to decipher Anchiornis’s color pattern.

Anchiornis had a crown of reddish feathers surrounding dark gray ones, and its face was mottled with reddish and black spots. Its body was dark gray, but its limb feathers were white with black tips.

Given the full detail of the findings, Dr. Prum said, “it was like writing the first entry in a Jurassic field guide to feathered dinosaurs.”

Luis M. Chiappe, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County who was not involved in the research, praised the rigor and detail of the new study. “For a dinosaur scientist, this is like the birth of color TV,” Dr. Chiappe said.

The color pattern of Anchiornis is reminiscent of living birds. A breed of chickens called Silver Spangled Hamburgs, for example, has white, black-tipped wing feathers. Dr. Prum speculated that studying these chickens might allow scientists to determine the specific mutations that gave rise to Anchiornis’s plumage.

The color pattern on Anchiornis was so extravagant that the scientists are confident it served some visual function. “It was definitely for showing off,” Mr. Vinther said.

Some features, like the crest, might have allowed the dinosaur to attract mates. But white and black limb feathers might have helped Anchiornis escape predators. A number of living animals like zebras use similar color patterns to dazzle predators, so that they can run away.

The researchers expect many more surprises as scientists look at other dinosaur fossils.

“There is a big chapter of dinosaur biology that we can open up now,” Mr. Vinther said.