Pachyderms find no mention in the Bible. So Professor Jodi Magness was astonished to uncover a mosaic in an ancient Galilean village’s synagogue which featured, of all things, a group of elephants.

Excavations at Huqoq began in 2011, and during the first season archaeologists led by Magness found the wall of a synagogue. In the subsequent seasons, Magness’s team uncovered portions of the Galilean synagogue’s mosaics. The part of the mosaic uncovered this summer, however, stunned archaeologists because it’s the first time they’ve found a synagogue decorated with a non-biblical story scene.

Magness, a professor of Early Judaism at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, spoke to The Times of Israel about her team’s latest discovery this summer: an enormous, ornate section of the 5th-century synagogue’s floor which tells a story in a mosaic. Which story, however, remains a subject of debate.

Huqoq, located just to the northwest of the Sea of Galilee, is mentioned as a border town for the tribe of Naphtali in the Book of Joshua, but was a Jewish agricultural village during late Roman and Byzantine times, when the synagogue was in use. The period is associated with the development of the Jewish law books known as the Gemara, and the village of Huqoq finds mentions in rabbinic texts as a producer of mustard and home to some significant rabbis. Stone vessels, mikvaot — Jewish ritual baths — and the synagogue attest to its Jewish habitation at this time. (Today there’s a modern kibbutz of the same name.)

“I had not anticipated finding mosaics, because the canonical type of Galilean synagogue does not have mosaic floors,” Magness said. Her aim when starting the expedition in 2011 was to determine when the Galilean-type synagogue, such as that found at nearby Capernaum, became the prevalent style, but the team had no idea a synagogue even lay beneath the earth before they started excavating.

They struck pay dirt. The eastern wall of the synagogue was found the first season; the first section of its mosaic floor was found in the summer of 2012, revealing depictions of Samson setting the Philistine’s fields ablaze with the aid of unfortunate foxes; and in 2013 a panel was revealed showing Samson carrying off the gates of Gaza.

Detail from the Huqoq synagogue’s 5th century mosaic showing Samson carrying the gate of Gaza, from Judges 16. (photo credit: Jim Haberman)

Samson alone would have been a remarkable find; he’s not a popular character in ancient synagogues (only one other example exists, found at Wadi Hamam, five miles south of Huqoq). But that was before Magness’s team found the first bit containing the elephants, and only in summer 2014 did they uncover the full extent of the section’s “really remarkable” decoration, as she put it.

“We have a dozens of ancient synagogues,” Magness explained. “But until now, none have been decorated with a non-biblical story.”

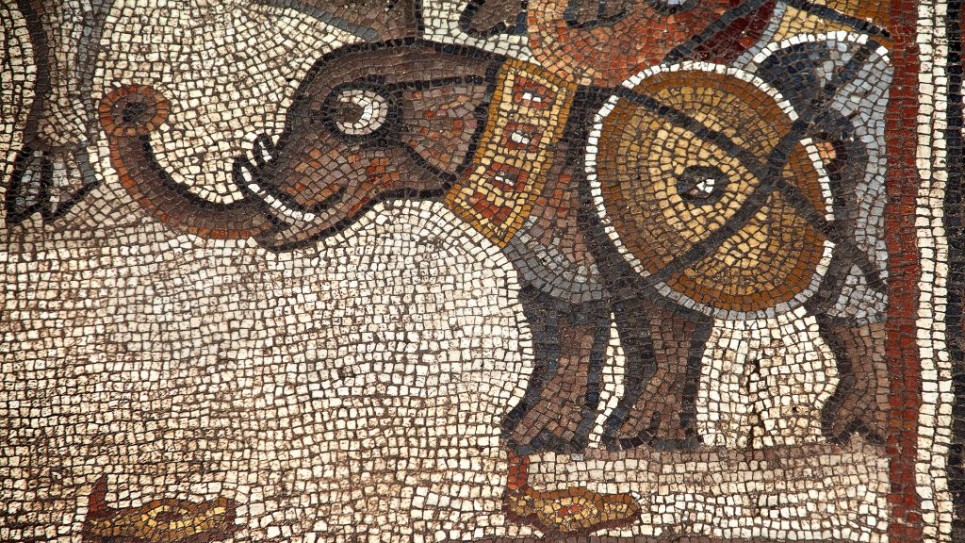

The top part contains two central figures, a white-bearded man clad in white robes and a Greek military commander with golden locks, dressed in regal purple and wearing a diadem. The old man, who appears in a lower portion of the mosaic as well, points at the sky and is flanked by an entourage of younger men in white robes with sheathed daggers. The Greek king leads a bull by the horns and is backed by a phalanx of soldiers and war elephants — a quintessentially Greek battle beast — with brilliant collars and shields on their sides.

“Elephants do not occur in the Hebrew Bible, there are no stories that involve elephants, so as soon as we had a story that showed elephants it war clear it was not a biblical story, and this is a first,” she said.

The lower section shows a dying soldier holding his shield and a bleeding bull bristling with spears.

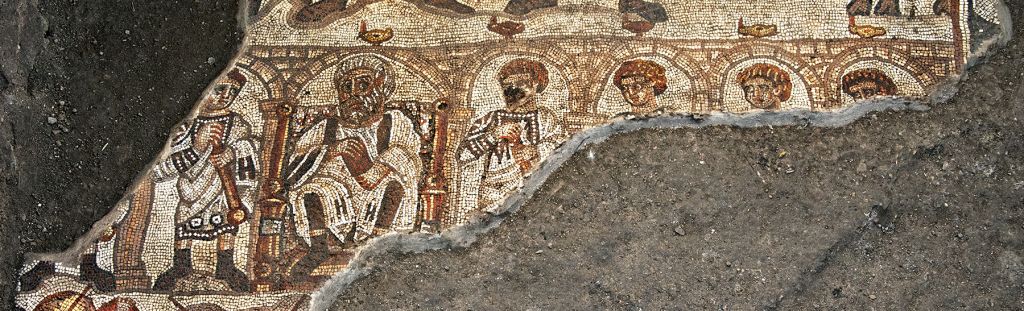

Detail of the Huqoq synagogue’s 5th century mosaic, showing the white-bearded elder. (photo credit: Jim Haberman)

The middle section shows the elderly man seated with a scroll in hand beneath a colonnade, flanked by young men with swords.

Detail of the head of a Greek military ruler in the Huqoq synagogue’s 5th century mosaic. (photo credit: Jim Haberman)

The entire scene, which has not yet been released, is “really remarkable,” said Magness, but scholars remain uncertain as to what precisely it depicts.

“We’re not releasing that entire upper scene [which includes the two figures and elephants] because it’s so extraordinary, and so amazing,” she said. “I have a mosaic specialist on my staff who is working with another scholar to prepare the publication of that in a proper manner.”

There are two contending theories for the time being. Last summer archaeologists postulated it represented the Maccabees facing off against the Seleucid Greeks, the wars commemorated in the Jewish holiday of Hannukah. While “that interpretation is still a possibility,” said Magness, she leans toward the panel telling the story of Alexander the Great’s legendary meeting with the Jewish high priest.

She emphasized that the sections of the ornate floor revealed thus far are but a small fraction of the entire mosaic, and the nave of the synagogue and its central design have yet to be uncovered.

“We don’t even know what’s in the central aisle,” Magness said.

Although graven images are proscribed in Orthodox Jewish tradition, the prevalence of human figures in this period — particularly in synagogues — reinforces the notion that there was a greater diversity in Jewish practice than suggested by historical texts.

“We tend to look at Judaism after 70 CE through the lens of the rabbis, because basically what we have is rabbinic literature for this period,” Magness said. “One of the things that we learn from archaeology is that in fact Judaism was far more diverse than what we would have anticipated from just reading rabbinic literature alone.”

For the time being the mosaics have been removed from the site for conservation and study and the synagogue filled in, so there’s no point in rushing up to Huqoq to try and see them in situ.